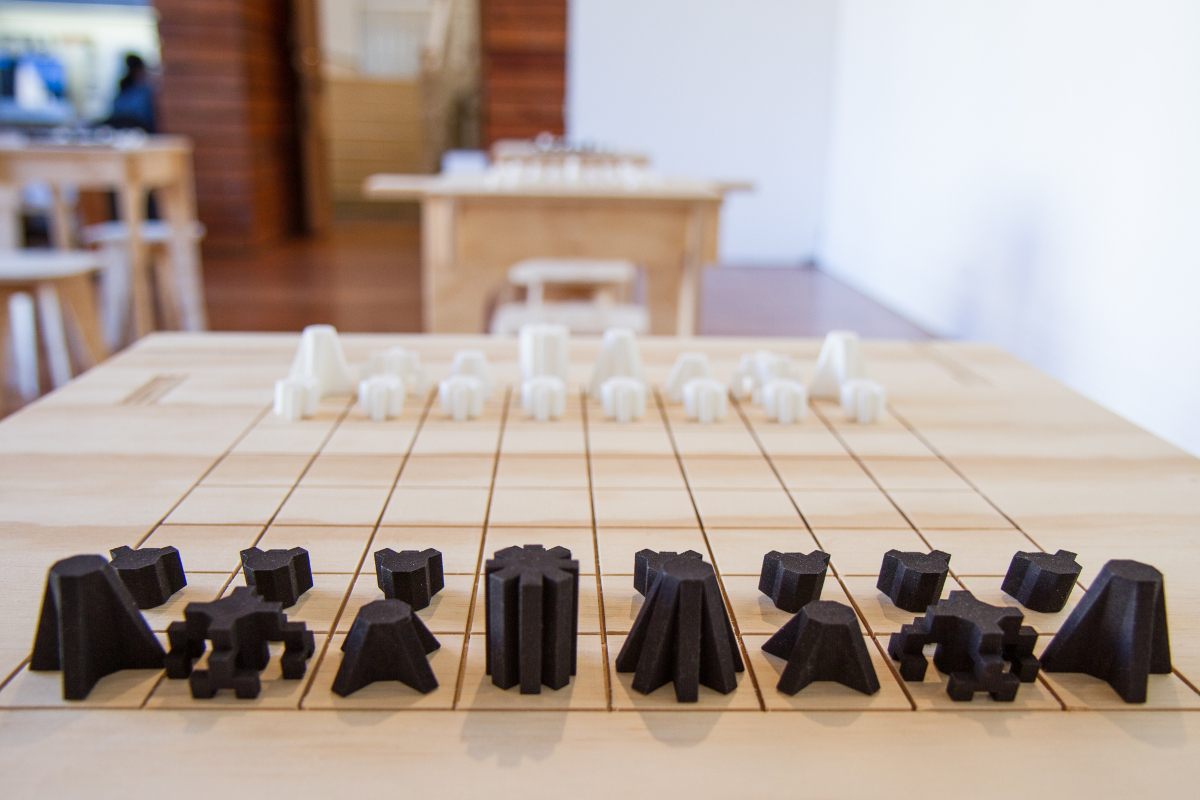

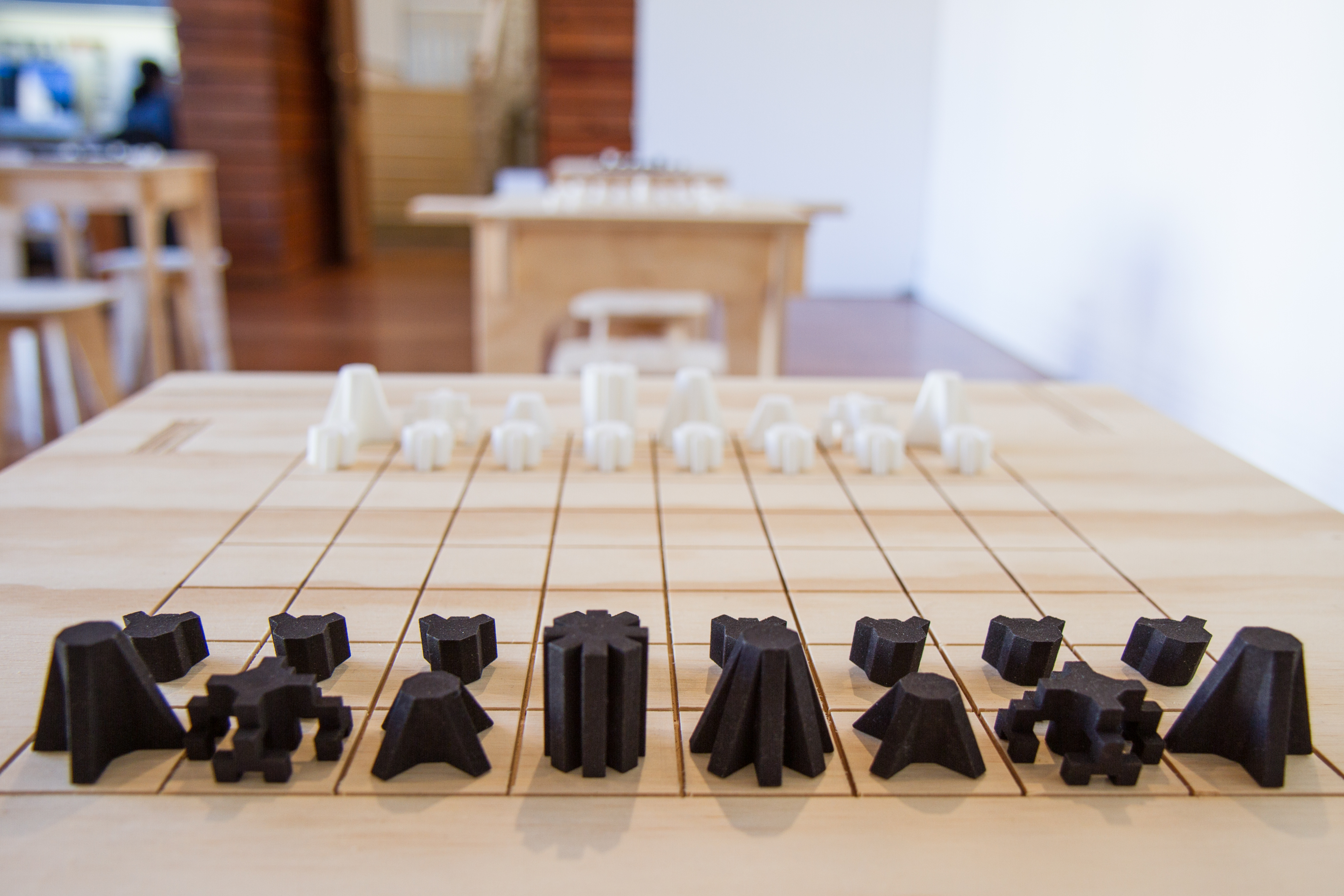

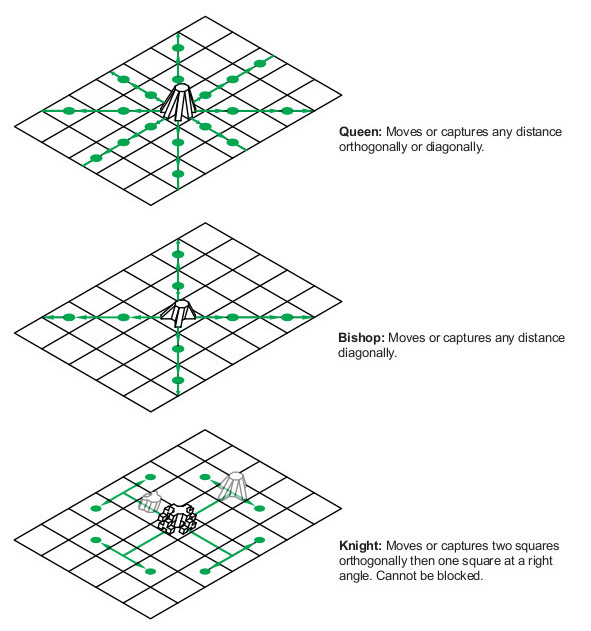

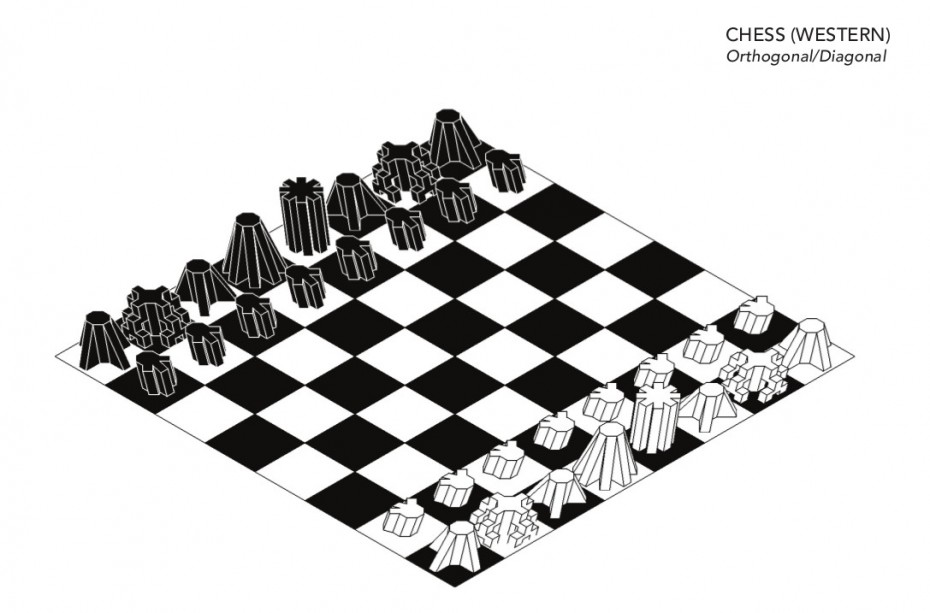

What if you could learn how to play chess simply by looking at the pieces? (more…) That's one of the ideas behind Orthogonal/Diagonal, an exhibition where artist Nova Jiang has reimagined chess with 3D-printed pieces designed to convey their rules of movement—and their relative importance on the board—at a glance.

"I remember having a lot of trouble learning checkers because the forms of the pieces didn't suggest their functions, so here, the instructions help you pick up the visual language," says Jiang. In other words, if an alien encountered the game for the first time, they'd be able to intuit some of the game simply by looking at it.

It's similar to the idea behind the Bauhaus chess set created by Joseph Hartwig in 1924, where the pieces convey their movements through clean, minimalist lines. Jiang's designs are a bit more intricate, thanks in part to the 3D printing process, which allowed her to make complex forms difficult to manufacture by hand.

The queen, for example, towers over the pawns, and splays outward in a many-pointed star shape that gestures at every direction it can move. The bishop is shorter and squatter, shaped more like an X to indicate its diagonal movement.

Jiang also created boards and pieces for seven regional chess variants beyond Western chess: Makruk from Thailand, Janggi from Korea, Shatar from Mongolia, Sittuyin from Myanmar, Shogi from Japan, Xiangqi from China, and Shatranj, a Persian and Arab predecessor to modern chess.

Many of the customized pieces she created can be used across multiple games, since all of the variants are derived from the ancient Indian game Chaturanga, and have analogous pieces and movements thanks to their common roots.

"Once I stripped away the culturally specific design for each variant, it became easier to focus on the underlying system and see how each variant evolved," says Jiang. Focusing on the universal aspects of the games can make it easier for new players as well, especially for those learning variants that involve characters from foreign languages.

"It's difficult to play Chinese, Korean and Japanese Chess if you can't read the characters used to mark the pieces," says Jiang. "Part of Orthogonal/Diagonal is about overcoming language and geographical barriers. Once you learn the visual language, then theoretically a Japanese Shogi player can have a friendly game of Mongolian Shatar with someone who's only familiar with Western Chess."

Jiang has invited chess players to try their hand at the different variants through her exhibitions in New Zealand, Austria, and most recently, at the UCLA Game Art Festival in Los Angeles. Despite the visual inuitiveness of the pieces, she still provides players with written instructions for each variant.

Although she loves the idea of the games being readable to completely new players—or alien civilzations—she notes that "players also really seem to like having instructions. I think the pieces work well as guides in addition to the instructions."

Orthogonal/Diagonal is also the first step in a longer-term project for Jiang, which involves developing software to generate abstract strategy board games and game pieces via artificial intelligence. Players would get to define some aspects of the game, an AI would create playable rules, and a script would generate game pieces that visually represent their movements.

"In my imagination, the project would help non-game designers like myself make unique board games," says Jiang. "Perhaps every visitor to a gallery where the software is shown can take home a 3D-printed game and become the world champion of their own special board game?"